Round 1

True to my principles, I didn’t check my opponent’s rating before the round. I had a strong start, catching my opponent off balance and creating a dense pawn majority in the center. However, more tension on the board means more complications, and I didn’t notice my Achilles heel until it was too late. He found it first, and my center evaporated. Only down a pawn, I already felt like I had lost – a prophecy which is always fulfilled. An [obviously] unsound tactic lost my knight and I was forced to concede a few dozen moves later. My 4th straight loss.

Round 2

I was buoyed by the fact that my previous opponent was rated 1900, so I wasn’t likely to have won anyways. I rallied for another game. I didn’t want to play anything too fancy, just get out some solid development and play some chess. Instead, I was met by a prepared line whose 2nd move was already a novelty to me (1. e4 e6 2. b3!?). Unlike my opponent, I didn’t know what was coming. It was a crushing defeat, which might’ve been even faster if my opponent was looking for tactics. My 5th straight loss.

I sulked back to the skittles room and sat in my chair. I wanted to quit. Chess was a dumb game, and I clearly wasn’t any good at it. My losing streak was mirroring my recent online losing streak; no end in sight. Maybe today just wasn’t my day. I was ready to withdraw and go home early. But I didn’t. I wallowed in self pity, while continuing my doodle. I hadn’t even bothered to take my ear plugs out, preferring the silence. The pizza box near me made my stomach rumble, but I just kept on doodling. Die another day.

Round 3

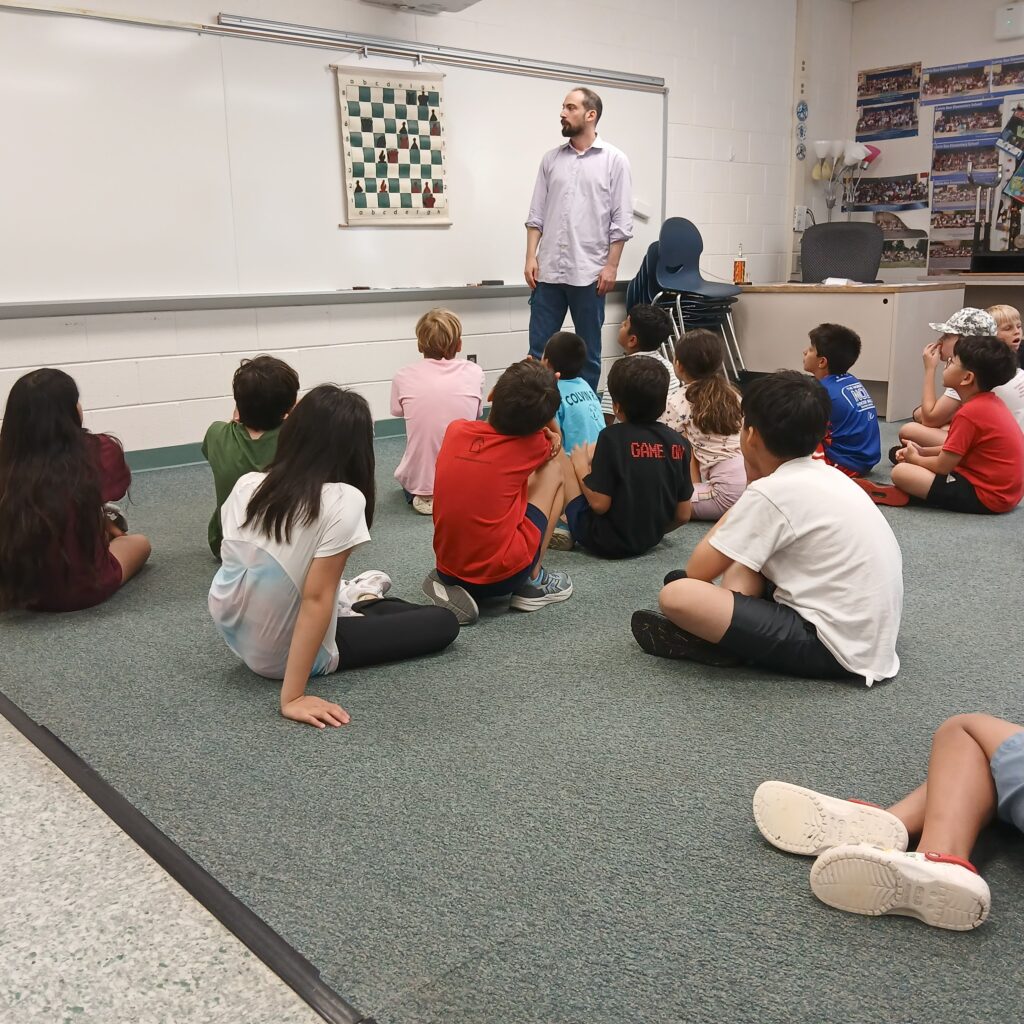

For the only time of the tournament, I was facing a kid. I had the bad luck of seeing his much higher rating, but I didn’t let it faze me. He played what I’m told is a London, which is silly because that’s a city. But, like all London players, he preferred his memorized development, and didn’t give much thought to locking out his dark square bishop, or my queen on b6. I sacrificed development to get him out of his comfort zone, causing him to eat up a lot of time. After every move he’d jump up and wander around the room, waiting for this stupid 1400 to discover she’d been beat.

But I hadn’t been beat. If I had just lost two games, so had he, and he was clearly more tilted about it than me. Experience has taught me to never underestimate your opponent, no matter her rating. He long neglected the critical push in the center, and allowed me to untangle myself. Soon enough, his passive pieces ran out of options, and more importantly, his clock ran low. I allowed him to panic into a mistake. To his credit, he played out the endgame, surviving on only seconds and his delay. He took the loss well, and my losing streak was broken.

Round 4

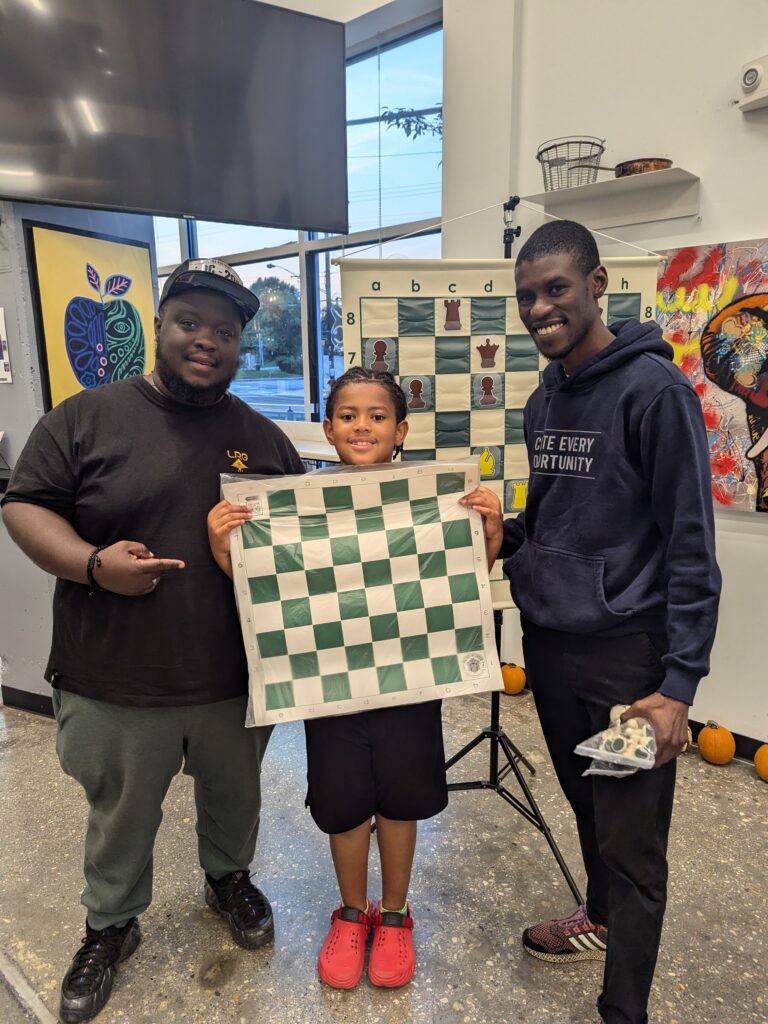

This round started at 8 pm, which meant I wasn’t getting home until almost 11 pm. My opponent played fast, so I did too. He opted for an unusual line, which allowed me a central passed pawn in exchange for a 2v1 majority on the queenside. If he wanted to quickly trade down into that endgame, fine by me. He let me blockade his pawns, which freed my rook from pawn duty to attack his king. I sacrificed Abby (my A pawn) for a rook on the 7th. The coup de grace came a few moves later, when my opponent, with still ⅔ of his time on the clock, blundered a mate in 1. It was the same mating pattern that I blundered (but wasn’t punished for) during a simultaneous game at White Oaks Elementary this past week. I not only finished with a respectable 2.0/4, but also clinched my highest rated win yet.