Fifty-one years ago this month, the chess match that changed the game forever began in Iceland, and since then that tiny island in the North Atlantic has been excited about the game. Iceland has had the most grandmasters per capita in the world since the 1970s and is unique in being the only country with more International Grandmasters (14) than International Masters (12).

In 2005, Iceland conferred citizenship on Bobby Fischer and sent a plane to retrieve him from Japan, where he was being held in custody at the demand of the United States. Fischer remained on the small island nation for the rest of his life.

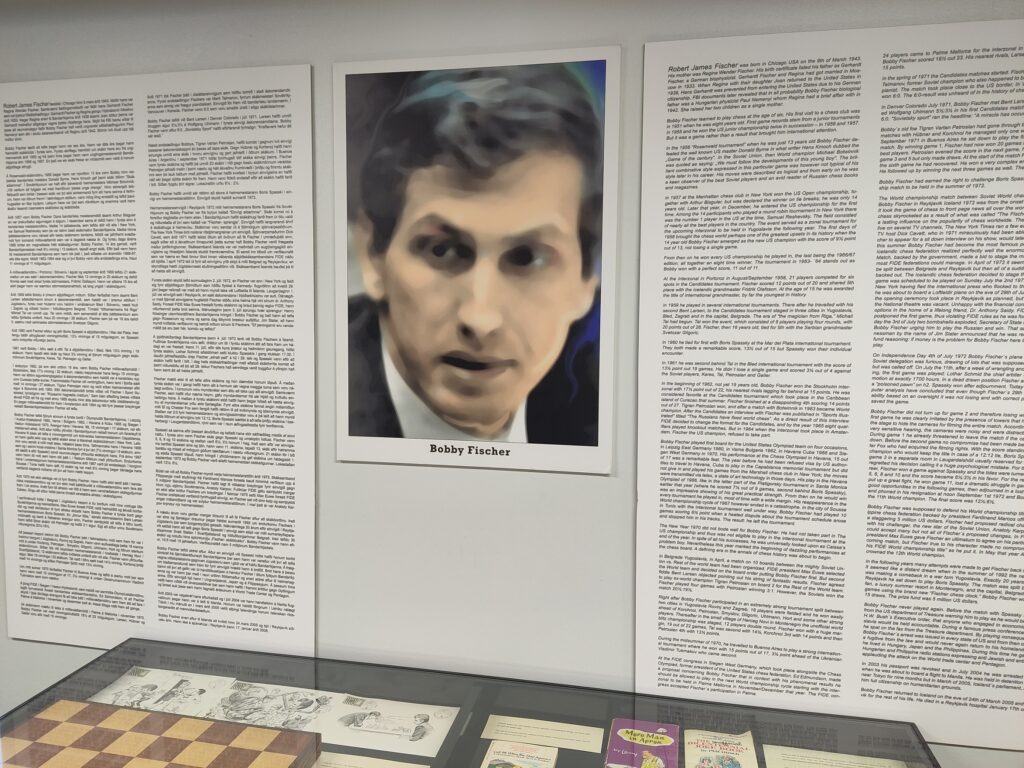

After he passed away, a group of chess enthusiasts created the Bobby Fischer Center near his final resting place in Selfoss. The Center celebrates Fischer’s life and chess career with particular emphasis on his connection to Iceland.

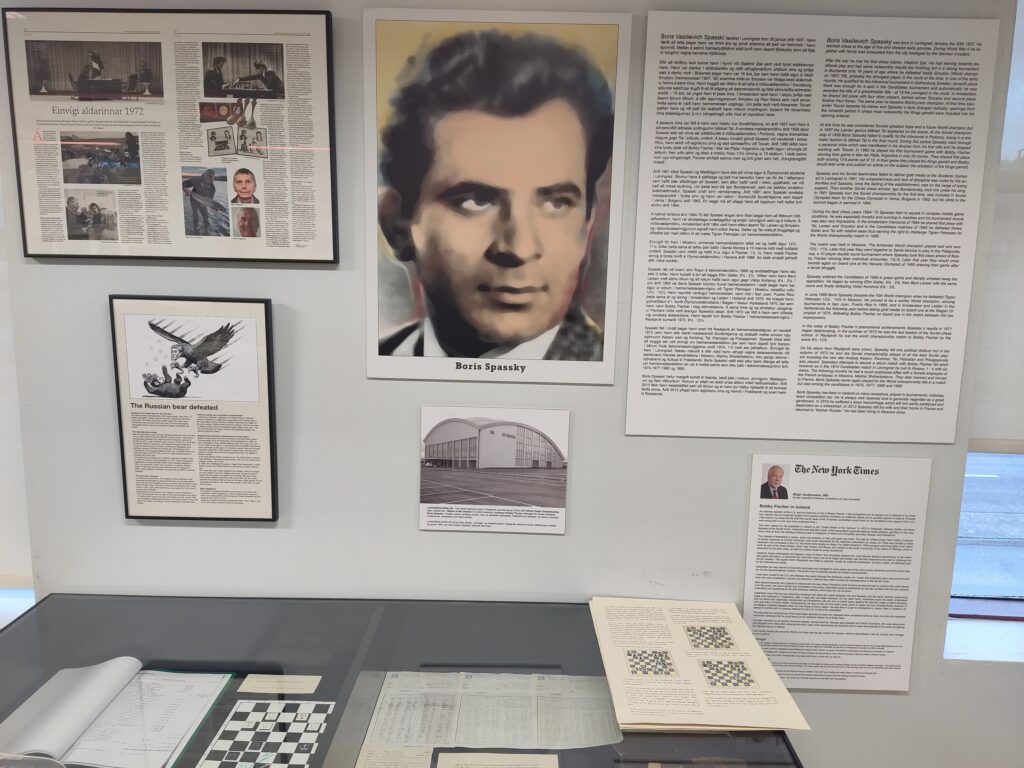

The 1972 match pitted the Soviet Empire, which had dominated high-level chess since the second world war, against a young American who eschewed assistance. Fischer knew the world champion, Boris Spassky, but had never beaten him over the board. He had lost three times while securing two draws in their previous matches. However, Fischer had gone on a record-setting run of victories leading up to the World Championship match, including winning 20 games in a row against players competing for the right to challenge for the world championship. Fischer’s international rating was 125 points higher than Spassky’s, a formidable difference.

The match attracted more attention than any previous chess match because of the international politics involved. Fischer made demands on the match organizers up until the games began, and for a while refused to travel to Iceland for the match. It took a series of efforts, including a call from the U.S. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger to implore Fischer to play the match and win for his country, to convince him to compete. By then, the match had been postponed for two days and the Soviet Union had to be persuaded to allow Spassky to compete after the insult of waiting for Fischer to arrive.

At last the match began, and the daily analysis of the games became the most-watched television in America. I had a personal stake in this, as it was in the run-up to the match that people asked me to teach them the game. It proved to be an avocation I would never relinquish.

The museum provides quite a bit of space to Boris Spassky, mainly about the 1972 match. It also covers their second match twenty years after the first, this time in the former Yugoslavia, which led to the indictment of Fischer for violating the U.S. embargo.

The Bobby Fischer Center also is used as a place to teach junior players. A substantial library of chess books is available for students to use, and there is space for about a dozen students at a time to play or receive lessons from volunteer grandmasters.

The Bobby Fischer Center is one of only three museums dedicated to World Chess Champions. (Emmanuel Lasker and Max Euwe are the other World Champions to have museums devoted to their memories.) Iceland is a fascinating and beautiful country, and chess players who travel there should make a point of visiting Selfoss, about 45 minutes outside Reykjavik on the Ring Road, and plan to spend an hour or two there.