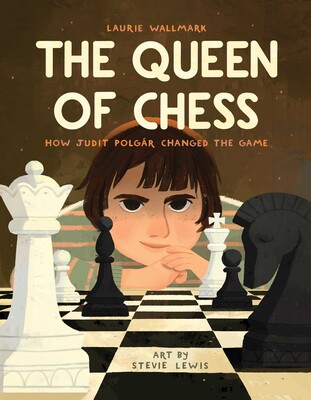

Book Review – The Queen of Chess

Judit Polgar is an inspiration to chess players throughout the world. The strongest female player ever, she is outspoken in encouraging girls, women, and children to learn to play chess.

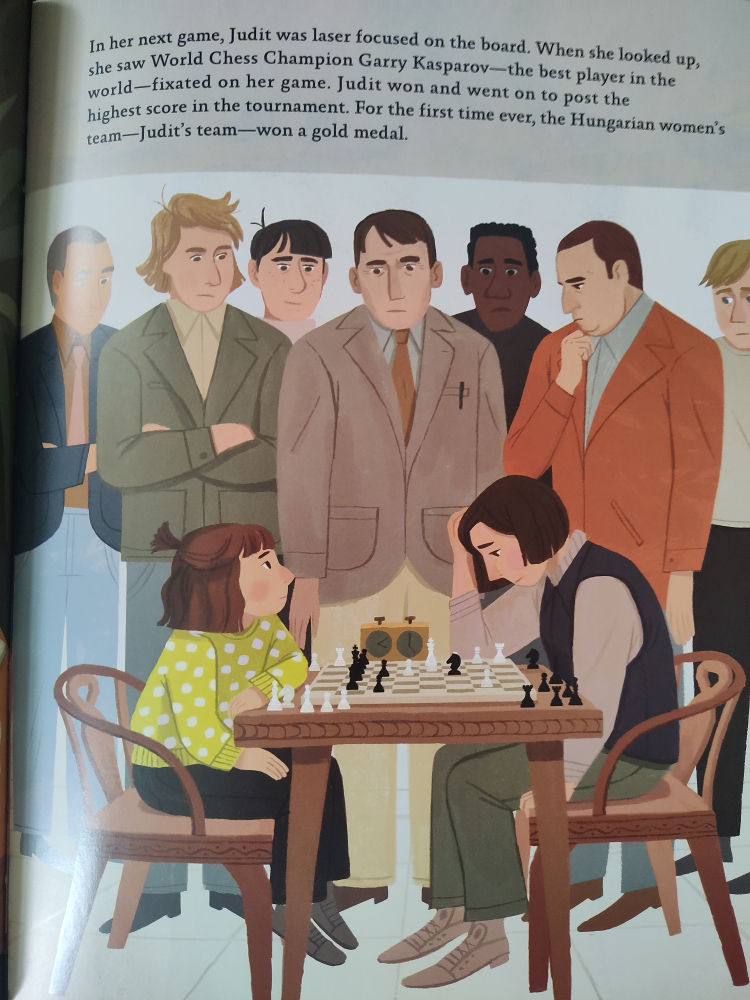

The Queen of Chess was written by Laurie Wallmark and illustrated by Stevie Lewis. Written and illustrated for children, this book avoids the problems many books about chess have faced. Polgar’s story needs no embellishment. She became an international chess sensation by the time she was nine years old, and during her career she defeated 11 World Chess Champions, including Garry Kasparov and Magnus Carlsen when each was ranked the best in the world.

The book takes its readers through her history, starting when she learned the rules of the game at age five. Children will be able to relate to her path and should find inspiration from the success that came from her dedication and hard work.

Appropriately, the book avoids all mention of controversies. There is no mention of the game she lost to Kasparov that was marred by his violation of the touch move rule. Later, Polgar beat him after he had suggested that she was a “circus puppet” and that women should stick to having children instead of playing competitive chess. Polgar faced discrimination both because she is a woman and because she is Jewish. That she overcame irrational prejudice in a game of logic and skill makes her journey more impressive, but it was good judgment to avoid those subjects in a book for children.

Polgar has written her own series of instructional chess books for children. Chess Playground, illustrated by her sister International Master Sofia Polgar, is in use in schools in her native Hungary and in China. https://www.juditpolgarmethod.com/

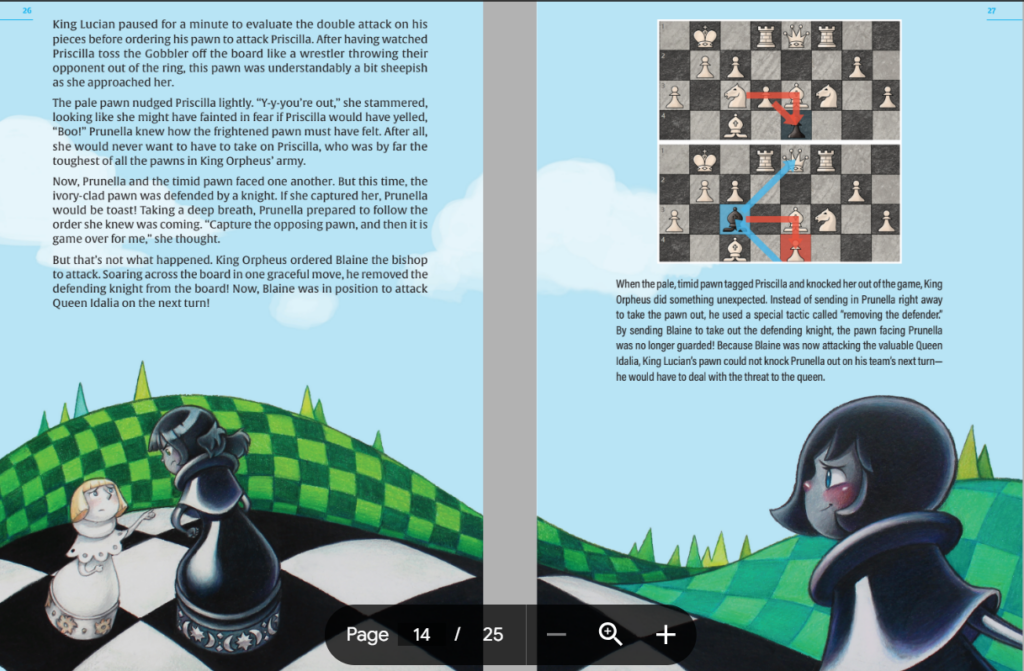

The Queen of Chess offers a few basics about the game and provides a puzzle that comes from a game Judit won at age nine. The book is not designed to teach chess but provides a wonderful introduction to one of the heroes of chess. Published by Little Bee Books, this book is a suitable gift for students in the primary grades (kindergarten through third grade).