By 1907, Frank James Marshall had established his credentials as the strongest active American chess player and among the best in the world. His victory in the Cambridge Springs tournament of 1904 was achieved with a dominant score of 13 points out of 15 games, well ahead of a world-class field that included World Champion Emanuel Lasker. However, this was several decades before the World Chess Federation (FIDE) began administering the World Championship and holding Candidates Tournaments to decide the challenger for the world title. In Marshall’s time, any player who wanted to challenge the champion needed to come up with the money for the match by himself. Lasker’s demand of around $5,000 – though negligible compared with the multi-million dollar prize funds of today – was an exorbitant sum for a chess match in the early 1900s.

To raise the money, Marshall turned to local chess associations in various American cities, each of which paid a portion of the prize fund in exchange for the right to host one or more of the games. One of those sponsors was the Washington Chess, Checkers and Whist Club. So, after the arrangements for the World Championship match had been made and the first eight games had been played at venues in New York City and Philadelphia, Lasker and Marshall would come south to the nation’s capital.

By the time the two players arrived in Washington, Lasker had gotten off to a dominant start, holding a lead of four wins to zero, with four draws. Since the rules at the time stipulated that the World Championship would go to the first player to win eight games, with draws not counting, Lasker was already halfway to retaining his title.

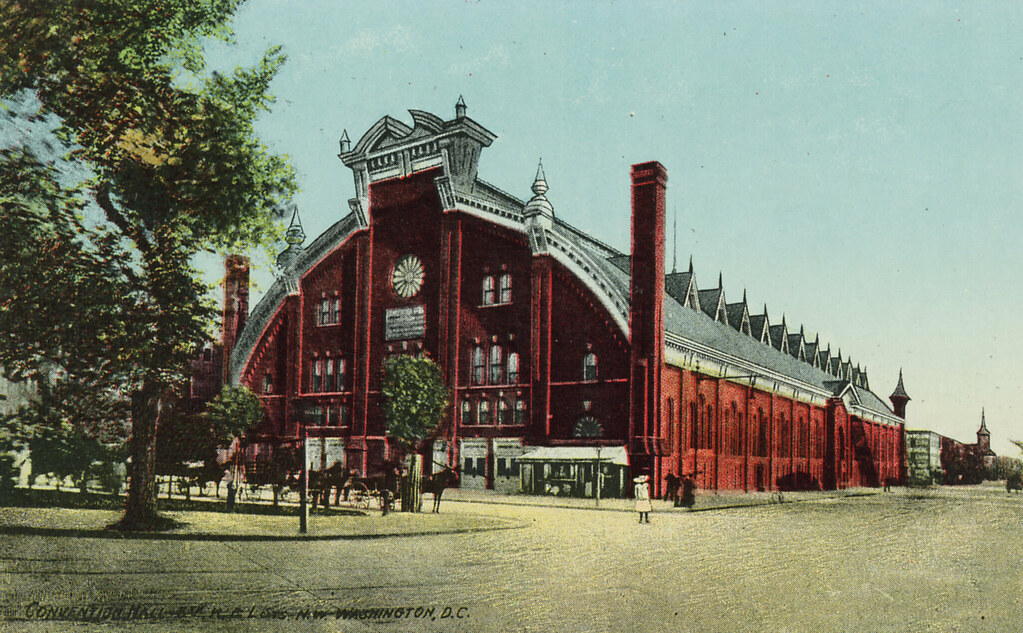

On March 2, Lasker and Marshall were hosted by U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt at the White House, and according to the Washington Star, both players felt that the experience more than justified the extra effort required to fit Washington into the travel itinerary. Afterwards, Game 9 of the championship match took place at Washington’s first convention center, then on 5th Street between K & L Streets, NW. Marshall played White.

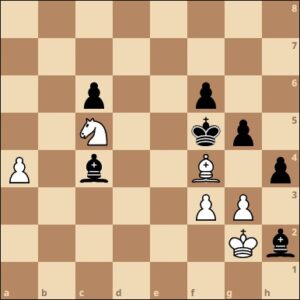

This was the position of the game after Marshall (White)’s 39th move. Lasker and Marshall’s contemporary Siegbert Tarrasch noted that Marshall had just erred by moving his king from f2 to g2 to attack the bishop, and Lasker could have obtained a winning advantage with 39…gxf4. Now 40. Kxh2 loses quickly to 40…fxg3+ 41. Kg2 Kf4, since White has no way to stop Black from forcing the f-pawn through with …h3+ and Bf1. 40. gxh4 Bg3 also loses for White, since he needs to give up his passed a-pawn to reclaim his lost piece, and after 41. a5 Bxh4 42. a6 Bxa6 43. Nxa6 Ke5 (centralize the king in the endgame!) 44. Kf1 Kd4, Black wins by carefully advancing the passed c-pawn. And after 40. g4+ Ke5, again Black wins with the centralized king and the passed c-pawn.

Instead, Lasker let the opportunity slip with 39…Bxg3? and after 40. Bxg3 hxg3 41. Kxg3 the game was drawn in a few more moves.

After both players agreed to a draw following White’s 46th move, Lasker and Marshall then made the short train trip to Baltimore for game 10, before playing the remaining games in Chicago and Memphis. The missed win in Game 9 was ultimately of little consequence to Lasker, who would wrap up one of the more dominant performances in the annals of World Chess Championship history by winning the match by a final score of eight wins to zero, with seven draws. In the years to come he would defend the title several more times before finally being beaten in 1921 by José Raul Capablanca.

For Marshall, it was a low point in what was otherwise a distinguished career in which he reigned as U.S. Champion from 1909 until 1936, founded the still-running Marshall Chess Club in New York, and remained an immensely popular presence in American chess circles until his death. He did not let his failure to secure chess’ highest title dampen his enthusiasm for the game. As he would remark much later in life, “I’ve been playing (chess) for over 50 years. I started it when I was ten, and am still going strong. In all that time I don’t believe a day has gone by that I have not played at least one game of chess – and I still enjoy it as much as ever.”